You’d be forgiven for imagining that Witney, David Cameron’s very own comfortable market town, has always been sleepy and dull. Didn’t it just make blankets for centuries and then become a pretty place for middle-class women to shop? Well yes, but it’s also had its fair share of drama. Here are five historical examples of Witney actually being totally screwed up.

WITNEY IS FULL OF… HOMICIDE

Well, when I say ‘full of’ I’m referring to one (particularly interesting) case, the Witney Axe Murder of 1871. It took right in the centre of town, in a cottage on Marlborough Lane, the little street to the right of the Blue Boar. It featured Edward Roberts and Anne Merrick – he was besotted with her, but she was reportedly cold towards him. One Sunday when she was cleaning the floor, Edward walked up behind her and hit her with an axe above the right ear. He then strode off to the Police Station (the front building of Henry Box School) to give himself up.

The Jackson Oxford Journal article about the incident included an account of Superintendent Cope, the officer who interviewed him:

“Roberts said “I loved that girl as I loved my life, and I hope her soul’s in heaven … see what jealousy will do; jealousy has done this.””

It didn’t take very long for the event to spark a folk ballad detailing the event. It began with:

“You feeling Christians pray attend,

And you shall quickly hear,

Of a most cruel murder,

That occurred in Oxfordshire.

And when the facts of this foul deed,

To you I do unfold,

It will make you start with horror,

And your heart’s blood to run cold.”

It was instantly successful in Witney itself, and according to the Witney Express it proved especially popular at that year’s Witney Feast.

“Ballad singers – who introduced with indifferent rhyme and questionable taste the persons and scenes connected with the late murder in Witney – drove an extensive trade.”

That can’t have been much consolation to Edward Roberts – he was hung in Oxford nine months later.

WITNEY IS FULL OF… DRINKING

Market towns usually have a lot of pubs due the large number of agricultural labourers who meet there, but Witney seemed to have an especially intense taste for booze. In the early 19th century, when the population was about 4000, there were thirty pubs and inns. During the 1950s Corn Street has a reputation for having more pubs on it than any street in Britain.

Things haven’t changed too much, although no longer the case due to several closures, in 2012 Witney had the same number of pubs as it did thirty years earlier – an almost unheard of case in modern Britain. Go us?

WITNEY IS FULL OF… WAR

Well, not full of actual battles or anything, but Britain’s various wars have left their mark on Witney. The nasty dynastic civil war of 1134 – 1154 (known by the badass name ‘The Anarchy’) prompted the Bishop of Winchester, the Lord of the area, to fortify the hell out of his palace with a moat and defensive fortifications. The ruins can still be seen, just next to St Mary’s church/Church Green.

The ‘proper’ English Civil War (1642 – 1651) placed Witney at the heart of things when Charles I made Oxford his capital. The Royalists made considerable demands on Witney’s resources, and hosted Charles and his army for a time. Charles stayed three nights in the White Hart pub, on the spot that now features the Witney Physiotherapy Centre on Bridge Street. It is thought that Cromwell himself may have passed through the town in 1649, but nobody knows for sure.

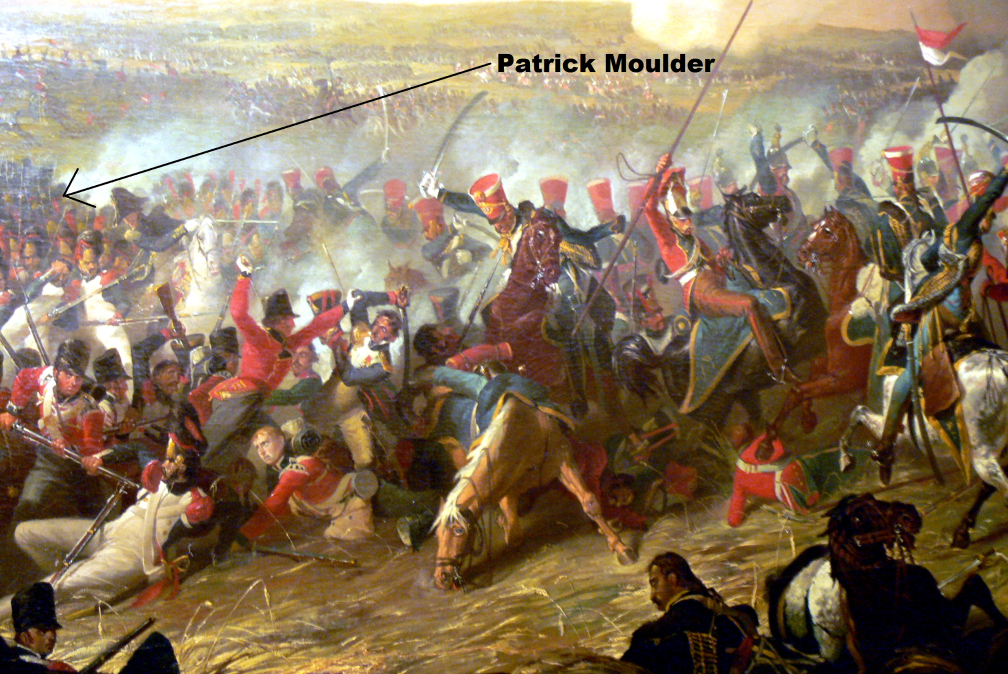

The massive campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) impacted Witney by hugely increasing demand for blankets and thus wool, but there’s a far more interesting Witney-based Napoleonic factoid. Patrick Moulder, a Witney citizen who ended up being landlord of the Cross Keys pub, fought through the entire war in the 15th Hussars, from the ignominious retreat at Corunna (1809) to the final victory at Waterloo (1815). Sadly, his story has a fairly tragic ending. In 1838 he shot himself in the head in the upstairs room of the pub – the servant who found him described that “his head [was] shot to atoms”. Despite the stigma of suicide his popularity in the town meant that he was buried with full military honours in St Mary’s churchyard. Over 3000 people attended.

The First World War had the same terrible effect on Witney as the rest of the country, but Witney did have some extra significance in the grand scheme of things. No. 64 Bridge Street housed a group of Belgium refugees fleeing the war and German prisoners were brought into the town to help the construction of an airfield on the ground now occupied by the industrial estate off Burford Road. Some American and Canadian soldiers were stationed at the airfield, and several baseball matches were played on the Leys.

Of course, the Second World War also hit Witney hard. The airfield was still used, so the skies above the town would often see Spitfires and Hurricanes. Witney itself was actually bombed once by a lone enemy aircraft – it didn’t kill anyone, but it did damage a number of buildings in the centre of town. Thirty-five of Witney’s young men were killed in the war, from the Far East to North-Africa, and six were killed in the fighting on and around D-Day. Some of those unfit for active duty formed a local Home Guard. According to the Oxford Mail, they participated in a simulated war exercise against imaginary airborne Germans:

“Much of the fighting was in West End and Mill Street, and it was in Mill Street that some tear gas was used, to the discomfiture of some pedestrians and motorists”.

Some military defences were set up in the town in case of an actual German invasion – a concrete pillbox can still be seen in Cogges guarding the river.

WITNEY IS FULL OF… REVOLUTIONARY FERMENT

It’s rumoured that some residents of Witney pitted themselves against the Industrial Revolution. The first mechanised wool mill in Witney was put in place on the banks of the Windrush (now known as Newmill, between Tower Hill and Crawley) – it proved to be destructive to the traditional methods of wool spinning, and caused much misery to local workers. The mill apparently caught fire three times and during the 1790s, Edmund Wright, the man responsible for introducing the mechanised system, plunged to his death in a pond nearby. Coincidences? I doubt it somehow.

A painting of Newmill in 1830. Don’t be fooled, it might look nice but it was actually a source of misery to many. Not those cows though, they look chill.

It might not seem massively important now, but Witney has also been very welcoming to nonconformist religious traditions. The founder of Methodism, John Wesley, frequently preached in Witney and had a great affection for the town and his large number of followers here. In 1783 Richard Rodda, one of Wesley’s travelling preachers, proclaimed to a crowd gathered at the Wood Green field: “My dear friends, take notice of what I am going to say: before this day next month you will hear and see something very uncommon.” Two weeks later there was a massive thunderstorm, and 84 townspeople became Methodists immediately – they were dubbed the“Thunder and Lightning Methodists”. Wesley’s mark in the town is still obvious, as well as the large Methodist church in the centre of town, the lane Wesley Walk was named after him.

WITNEY IS FULL OF… TRAGIC SCENES OF DEATH AND MISERY

No I’m not referring to a night-out in Nortons, I’m talking about an event that took place in 1652. A group of ‘mummers’ (a group of actors who would travel around performing bawdy plays) rocked into Witney and tried to hire a public space for their performance, but the town authorities deemed them unsuitable for public consumption. They ended up performing in the upstairs room of the White Hart (the same pub Charles I stayed in a couple of years before), but after an hour the floor collapsed, crashing the occupants of the room into the packed pub below. Five people were killed and sixty were injured. A prominent local Puritan John Rowe repeatedly preached that this was a punishment from God aimed at the impure nature of the performance.

So there we have it, indisputable proof that Witney has a history as meaningful and bizarre as anywhere else. Things aren’t exactly boring now, only last week a local man scared off some sledgehammer-wielding burglars with his sword.

Will Hazell

Special thanks to Charles and Joan Gott, authors of The New Book of Witney and Joe Robinson, author of Oxfordshire Ghosts.

If you’re cool, follow me on Twitter.